The Knowledge Stack: Claude Cowork and the Future of AI Work

Introduction: A 100-Page Design Doc in 3 Days

Last week I produced a 100+ page technical design doc in about three days. This felt like a high point of my career.

The xoogler sits down to write his longest design doc yet.

That might sound dramatic for a design doc, but hear me out. At Google, I was what you might call a “doc-writing engineer.” I’d produced large technical documents before, and I know what the process usually looks like: weeks of discussion, drafts, feedback, alignment meetings, more drafts, on and on. A doc of this scope would normally take 2-3 weeks. This one took three days. And while it came together really quickly, it certainly met the quality bar too. We’re already in our hyper-productive future.

The doc required synthesis across multiple sources. I worked in ChatGPT, using its connectors to pull context as needed. But the experience was far from seamless, and getting the output into its final form was another story. The amount of time I spent just formatting the thing was absurd. It made me dream of a workflow where I could stay locked into the parts of the process that actually mattered.

This pattern isn’t unique to design docs. Grant proposals, regulatory filings, government contracts, legal briefs, policy white papers: any large document that synthesizes multiple sources and must maintain internal consistency faces the same challenges.

So that’s what I want to talk about today. In this post, I’ll walk through what worked, what didn’t, and what I think the future looks like. I’m calling it the knowledge stack, and it treats documents the way we already treat code.

How the Design Doc Actually Happened

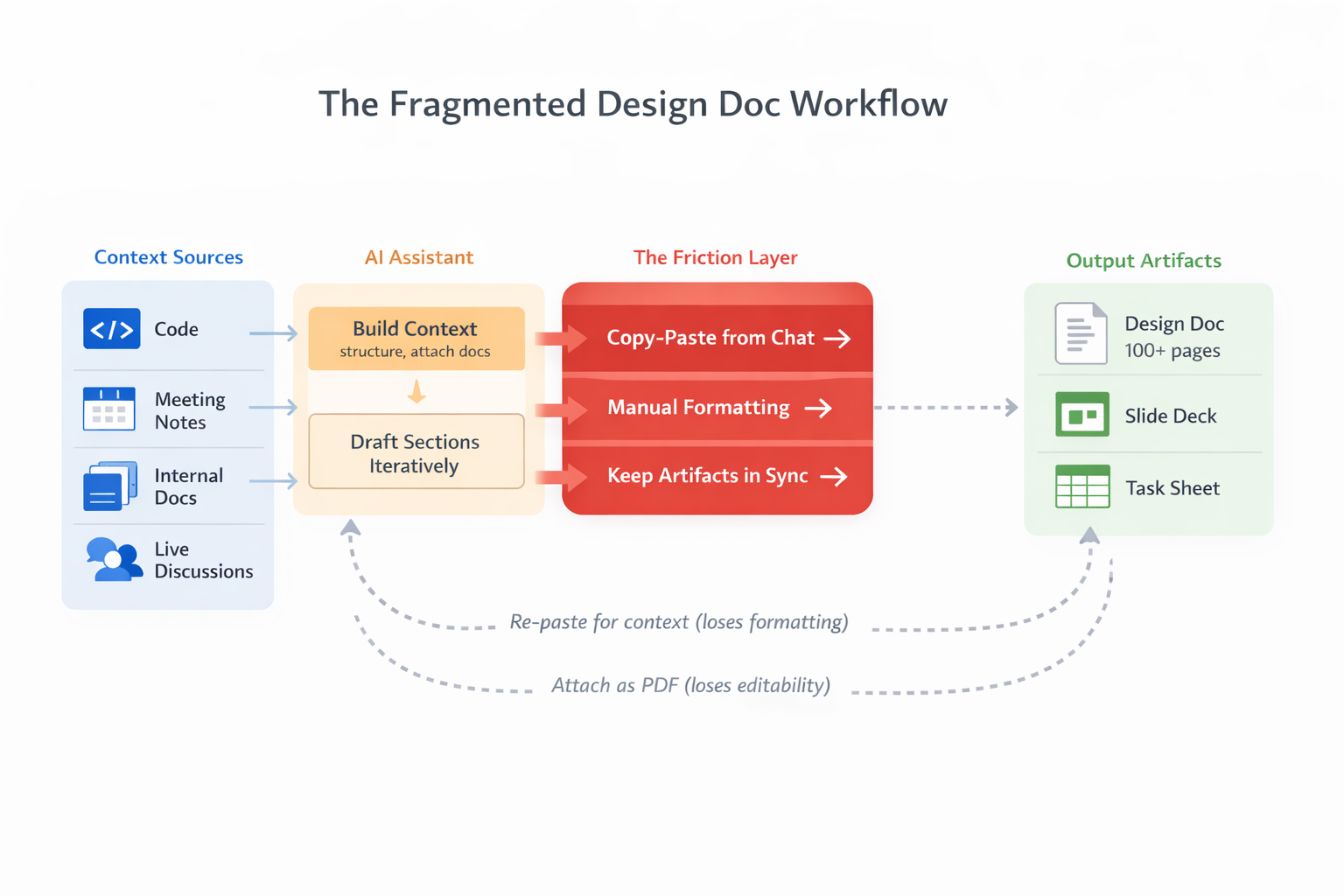

A rough outline of the workflow I used: context sources on the left, friction in the middle, outputs on the right. Note the dashed arrows looping back as I constantly rebuilt context.

The Good: Context on Demand

The doc had a high-level structure from the start: several major sections were requested in the original doc template, and each could be built out further with repeated subsections. I drafted within each subsection, and each subsection was a reasonable number of paragraphs, building context progressively. This meant I could catch errors early and accelerate as I went. By the time I hit the later sections, the AI already understood the vocabulary, the constraints, and the decisions I’d made.

The connectors were essential. When I needed to understand our current infrastructure, which is all written as code, I pulled from GitHub. When I needed to reference an idea that we discussed in a meeting earlier in the week, I grabbed the notes from Fellow, my company’s AI meeting assistant. When I needed to align with prior decisions, I accessed our Notion docs. Connectors handle all of this context management quite elegantly, and it sped me up considerably.

The Bad: The Copy-Paste Tax

The final output had to live in Google Docs and follow a preset formatting style. Along the way, I also needed to produce a companion slide deck for a doc review meeting, and last, I made a spreadsheet to track the implementation plan. That list of tasks was the original source of truth for what would get done. Work on these different assets required a lot of context switching, with the high chance of them falling out of alignment. Change some text, then you need to go track down something in the deck or the sheet to make sure the right information is there too.

None of these could be written directly by the AI. Part of that is an organizational constraint; we don’t give Drive access to ChatGPT. Part of that is due to the fact that these stacks still don’t work well together. So instead, the workflow became:

- Draft a section in ChatGPT

- Copy to Google Docs

- Fix headings, tables, spacing

- Update the relevant slides

- Check that the spreadsheet and deck is still aligned

- Repeat

Each round trip cost time and attention. By the end, I estimated that I spent more time on formatting than on anything else. The low-value work had consumed the majority of my effort.

Even though this remains my top complaint, there’s a caveat here. When AI-assisted work moves this fast, there’s a real risk of losing situational awareness: the human loses connection to the output, stops understanding what’s actually being produced. Even though the formatting grind felt tedious, it had an upside. It forced my attention onto the doc. It gave me the opportunity to read what the AI had written, catch errors, and edit. The low-value work, paradoxically, kept me in the loop.

The Ugly: Context Decay

ChatGPT manages its own context window. As conversations grow longer, earlier information fades. I compensated with workarounds:

- Copy-pasting large sections of the doc back into chat, losing formatting in the process

- Attaching documents as PDFs so the AI could reference them

- Wrapping pasted content in XML-style tags like

<section>,<requirements>,<constraints>to help the model parse structure - And repeating these tricks whenever something started to seem weird

This all helped, but the process was quite brittle. The fundamental problem is that the chat, which ultimately was geared towards producing the document, didn’t have state in the way a file on your computer has a state. I sometimes had to start a new chat because ChatGPT became unresponsive from the amount of text in previous parts of the conversation. Those new sessions started from scratch, requiring me to rebuild the context and hope that choices from previous conversations carried over.

What Claude Code Gets Right

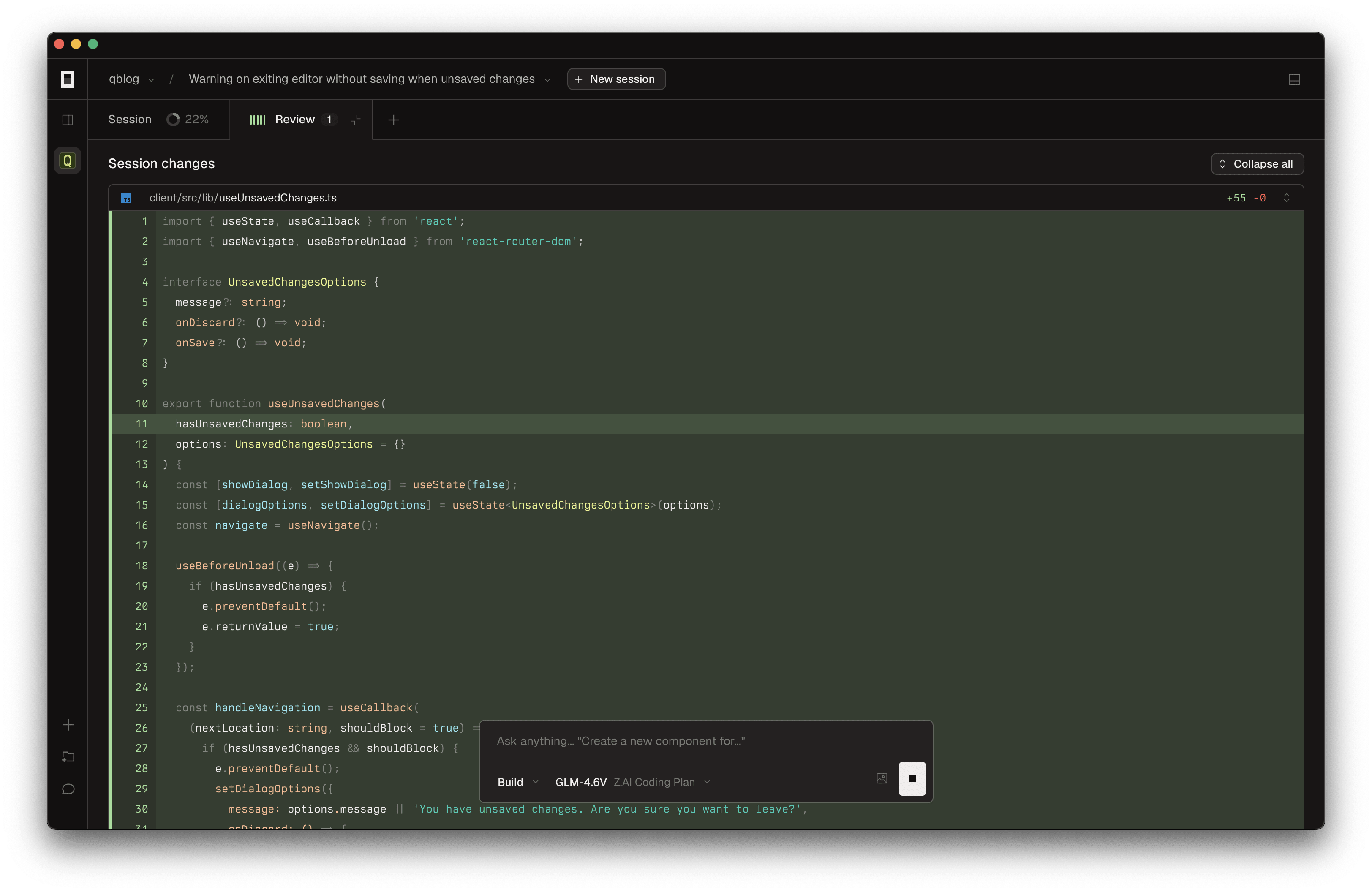

When I code with Claude Code or OpenCode, the experience is fundamentally different from the design doc workflow.

Persistent state. Work happens in local files. I can checkpoint, branch, and diff. When I return to a project the next day, everything is where I left it. OpenCode does a great job of tracking sessions too, so you can quickly hop back in.

Visible progress. When writing code, I see small edits applied incrementally. Each change is presented as a diff before it’s applied. I can interrupt, redirect, approve, or reject. The review step is built into the flow, not something I have to bolt on afterward.

Tool integration. Formatters run automatically. Tests provide feedback. Linters catch errors before I even see them. The agent operates within the same ecosystem of tooling that I’d use manually.

The loop. These products all reinforce the knowledge work loop: perceive, reason, act, adapt. This cycle happens naturally because the file system is the shared source of truth. The agent proposes, I review, we iterate. I stay in the loop without having to do busywork to maintain situational awareness.

The key difference is simple: the file system is the working state. It doesn’t disappear when the conversation ends. And because the state is visible, diffable, and persistent, the review process keeps me connected to the work.

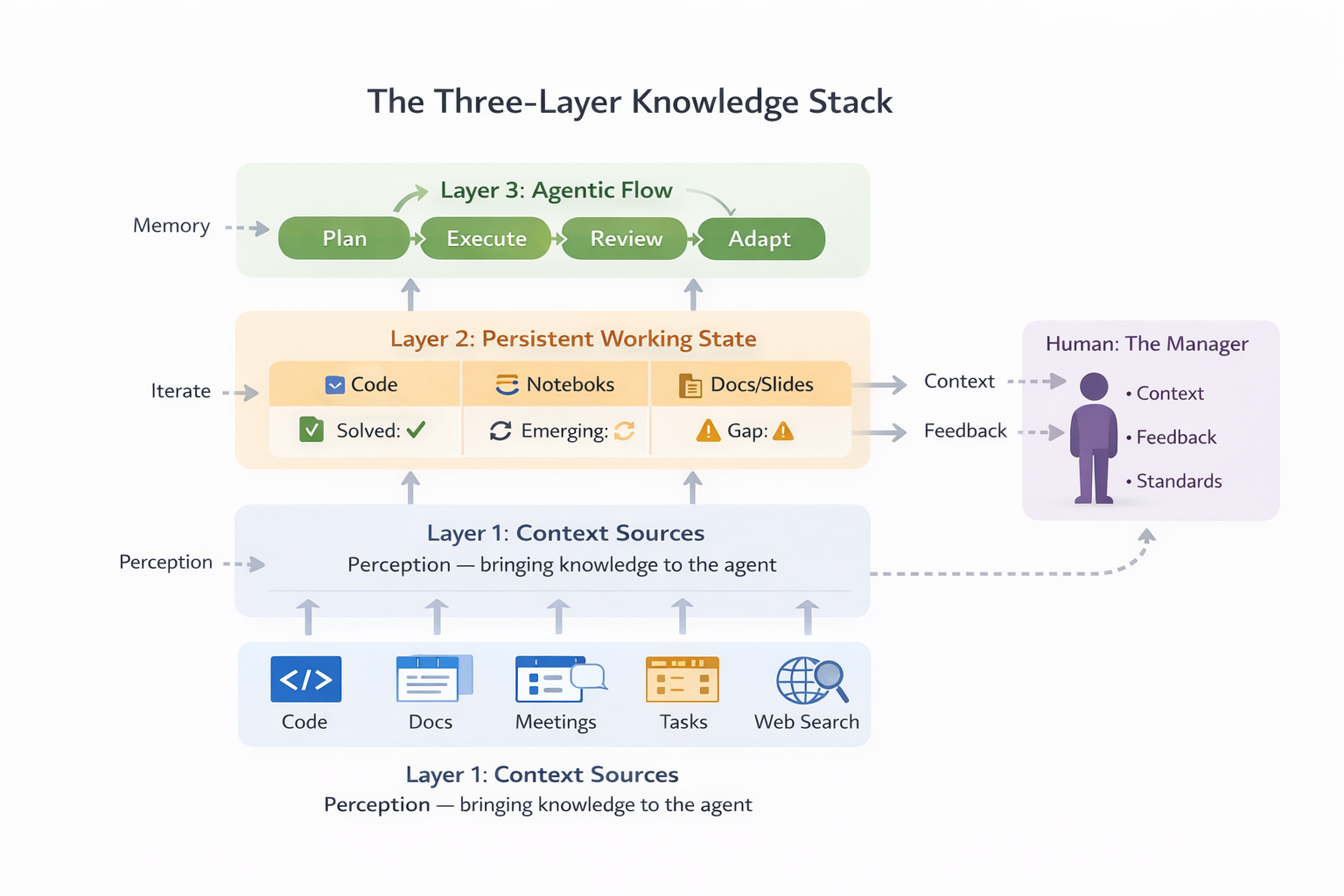

The Knowledge Stack: A Framework

If Claude Code works so well for coding, what would the equivalent look like for knowledge work more broadly? I think of it as a three-layer stack.

The knowledge stack: context sources feed persistent state, which enables the agentic flow. The human stays in the loop as manager.

Layer 1: Context Sources

This layer is already here. MCPs and connectors make knowledge accessible: GitHub, Notion, Fellow, Linear, web search, and more. This is the “perception” step of the loop. The agent needs information to do its job, and these tools bring it in.

My design doc workflow relied heavily on this layer, and it worked. I could pull from our codebase, our meeting notes, our internal docs. The problem wasn’t access to context. The problem was everything that happened after.

But access alone isn’t enough. Context is a finite resource. Anthropic calls it an “attention budget”: as the number of tokens in the context window increases, the model’s ability to accurately recall information decreases. Every new token depletes this budget. The challenge isn’t just getting information into context. It’s getting the right information in, at the right time.

One pattern I found myself using constantly: summarize first. Before asking the agent to incorporate a repo, a long meeting transcript, or a dense requirements doc, I’d prompt it to produce a quick summary. This felt like calibration. The summary forced the agent to identify what mattered, and it gave me a checkpoint to verify we were aligned before moving forward. If the summary missed something important, I could redirect before wasting tokens on the wrong path.

This is a form of what researchers call progressive context building. Rather than dumping everything into context upfront, you start with a compressed view and expand selectively. The agent loads lightweight references first, then drills into details on demand. Anthropic’s Claude Code uses this approach: it maintains file paths and identifiers, then uses tools like grep and glob to retrieve content just-in-time rather than preloading the entire codebases.

The summarize-first pattern works for knowledge work too. When incorporating meeting notes, start with “summarize the key decisions and action items.” When pulling in a requirements doc, start with “identify the top 5 constraints.” When analyzing a competitor’s product, start with “what are the three most important differentiators?” Each summary becomes a focusing lens for the work that follows.

Layer 2: Persistent Working State

This is the gap.

Code has files. When an agent writes code, it writes to a file. That file persists. I can diff it, version it, branch it, come back to it tomorrow. The file system is the working memory. Other files, like AGENTS.md, can be used to build long-term memory.

What do documents have? Google Docs, Slides, and Sheets. Word, PowerPoint, and Excel. These tools became the standard for knowledge work because they’re optimized for human collaboration: sharing, comments, real-time editing, version history. For working with other people, they’re excellent.

But they’re not designed for agents. There’s no simple text file to write to that persists outside the app. There’s no diff primitive. There’s no way for an agent to checkpoint progress and resume later. The state lives inside the application, managed by the application, inaccessible to the agentic flow.

This is why the copy-paste tax exists. Until documents have the same kind of persistent, file-based state that code enjoys, the friction remains.

Some approaches are emerging, and I’ll cover them below. But first, let’s look at what makes the agentic code workflow so effective.

Layer 3: The Agentic Flow

This is the loop: Plan → Execute → Review → Adapt.

What makes Claude Code effective at this:

- Structured task breakdown. TODO lists, scratchpads, incremental planning.

- Small diffs for review. Each change is visible before it’s applied.

- Interruptibility. You can course-correct at any point.

- Feedback loops. Tests, linters, user approval. The agent gets signal on whether its work is correct.

What’s missing for knowledge work? There’s no natural “diff” for a paragraph. No “test” for a slide deck. The review step requires the human to hold everything in their head, or to impose structure manually. This is solvable, but we’re not there yet.

The Subagent Pattern

There’s another dimension to this that I’ve been experimenting with while writing this post: subagents.

Claude Code has a PR Review Toolkit that bundles six specialized agents for code review: one for comment accuracy, one for test coverage, one for silent failures, one for type design, a general reviewer, and a simplifier. Each agent gets a focused prompt and a limited view of the codebase. The idea is that specialization improves quality. A test coverage agent thinks only about tests. A silent failure hunter thinks only about error handling.

But there’s a subtler benefit: fresh perspective.

When you work with an agent in a long session, you accumulate shared context. The agent knows your decisions, your constraints, your vocabulary. This is useful for drafting. It’s less useful for review. An editor who knows too much about your intentions may fail to see what’s actually on the page.

The subagent pattern inverts the usual context management story. Instead of maximizing what the agent knows, you deliberately limit it. You spin up a new agent with just the artifact and a focused prompt: “Edit this for clarity. Flag any logical gaps.” The subagent doesn’t know your prior reasoning. It reads what you wrote, not what you meant to write.

I used this pattern while drafting this post. After completing a section, I spawned an editor subagent with only the draft and my style guide. It caught a duplicate sentence I’d missed, flagged overused phrases, and suggested structural improvements. The context denial was the feature. Because the editor didn’t know my thought process, it could read with fresh eyes.

This matters for the knowledge stack. Feedback doesn’t have to come from tests and linters. It can come from specialized agents with deliberately constrained context. The manager’s job expands: you’re not just directing one agent. You’re orchestrating a team of specialists, each with the right view for their task.

The Ralph Wiggum Loop

To see what becomes possible when all three layers work together, consider an extreme example from software engineering. Geoffrey Huntley has a concept he calls the Ralph Wiggum loop. In its purest form, it’s a bash loop:

while :; do cat PROMPT.md | claude-code ; done

Ralph is an agent running continuously, building software while you sleep. It makes mistakes. It goes off track. But the mistakes are “deterministically bad in an undeterministic world,” as Huntley puts it. When Ralph does something wrong, you tune the prompt. You add a sign next to the slide saying “SLIDE DOWN, DON’T JUMP.” Eventually, Ralph learns to look for the signs.

This works because of the stack. Ralph has context sources it can query. Ralph writes to files, which persist. Ralph operates in a loop where it plans, executes, and adapts. The feedback comes from tests, linters, and the human reviewing the output. I wrote about the importance of these feedback loops in agentic development previously. Huntley ran Ralph for three months, and it created a new programming language. Someone else used Ralph to deliver a $50k contract for $297 in compute.

The Ralph loop illustrates the potential we have in software engineering. The stack is complete enough that you can put an agent in a loop and walk away.

Now consider knowledge work. Could you run a Ralph loop to write a design doc? A grant proposal? A regulatory filing? Not yet. The persistent state layer is missing. And as I’ll discuss later, so is the feedback layer.

That’s the missing piece. And that’s what the emerging tools are starting to address.

What’s Being Built: Claude Cowork and Beyond

This problem isn’t going unnoticed. Several tools are starting to address it, each tackling a different part of the stack.

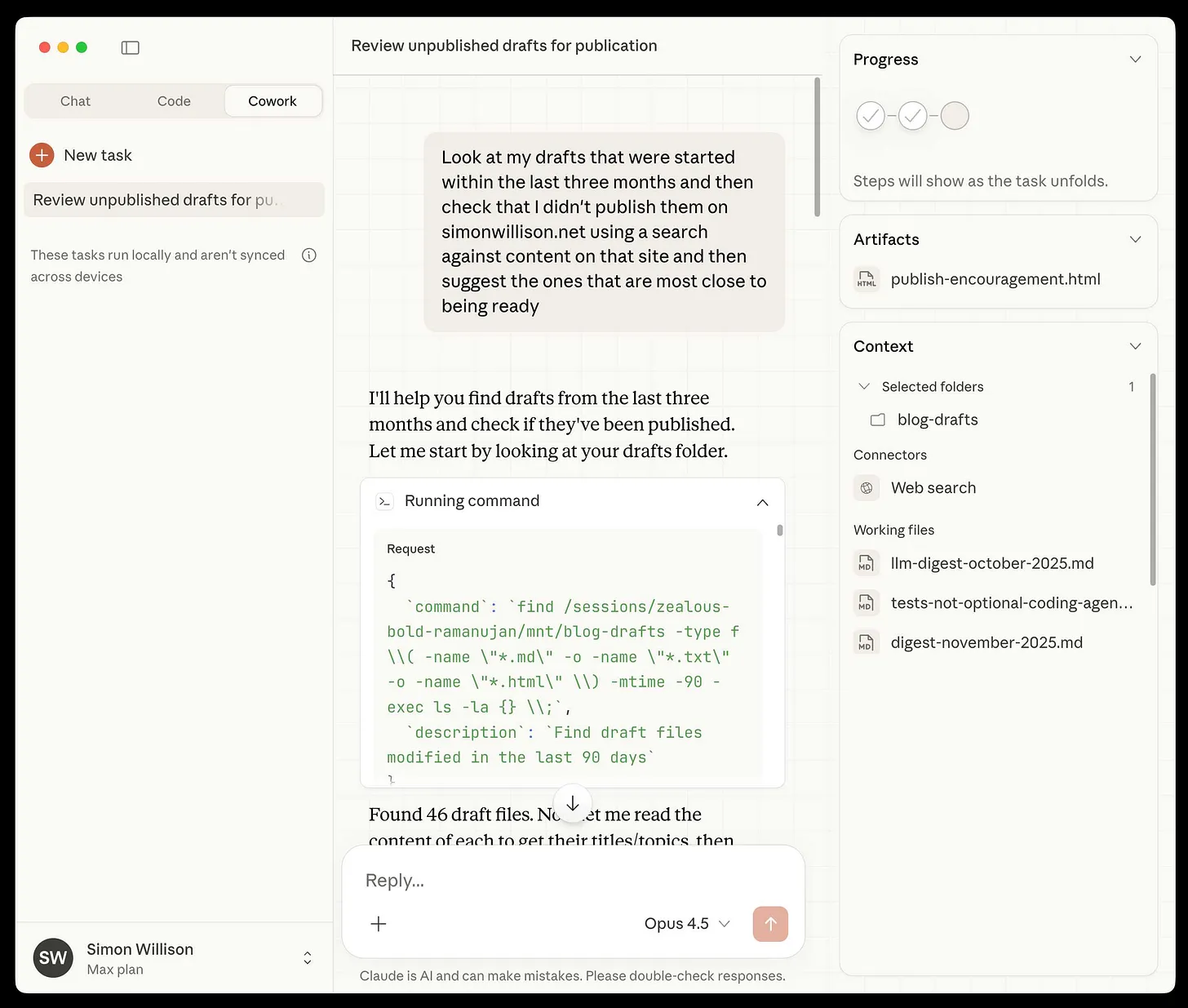

Claude Cowork

Anthropic announced Claude Cowork on January 12, 2026, scooping me by a little more than a week. It’s now available to Pro subscribers for $20 per month and represents Claude Code’s architecture applied to non-code work.

Screenshot from Simon Willison’s Newsletter

The setup: you grant Claude access to a designated folder on your Mac. From there, it can organize files, create spreadsheets from screenshots, draft reports, and build slide decks. It operates with multi-step planning, file-based state, and minimal supervision. You give it a task, it works through it, and you review the output.

This is exactly the model I wanted for my design doc. Instead of copy-pasting from chat to Google Docs, I could have pointed Claude at a folder of markdown files and let it draft, revise, and structure. The file system becomes the working memory. The review happens on diffs, not on re-reading entire documents.

Cowork is still in research preview and macOS-only, but the direction is clear.

Jupyter MCP and Notebook-as-State

A colleague at Delphos has been experimenting with Jupyter MCP to maintain state while developing notebooks with an agent. The pattern is elegant: the notebook is the memory.

Variables persist across sessions. Execution history is preserved. The agent can run code, see outputs, debug errors, and iterate, all without losing context. This works because notebooks are a hybrid format: code, prose, and outputs in a single structured file.

For data science workflows, this is promising. The notebook serves as both the working state and the artifact. There’s no copy-paste tax because the agent writes directly to the thing you ship. This is Layer 2 solved for a specific domain: persistent, structured, and accessible to agents.

Google Colab seems to be going in a similar direction. The most recent version ships with a chat box at the bottom, and you build out the notebook over the course of the conversation. The results of each interaction are kept right in front of the user. Colab’s biggest limitation right now seems to be the model lock in, but Gemini will eventually be good enough for this to not matter much.

OpenCode and the TUI Pattern

The terminal UI pattern has become central to agentic development. Claude Code, OpenCode, Aider, and others all follow a similar model:

- Files are the source of truth

- Diffs are reviewable before they’re applied

- Skills, commands, and MCPs extend capabilities

- The human is in the loop but not in the way

I use OpenCode daily. As a matter of fact, it’s how I’m drafting this post. The experience is what I described earlier: persistent state, visible progress, interruptibility. The TUI pattern works because it puts the file system at the center and builds the agentic flow around it.

OpenCode Desktop is coming soon, bringing the same workflow to a GUI. For those who prefer windows over terminals, this will lower the barrier to entry.

Screenshot from Ashik Nesin

What About Gemini and Copilot?

The incumbents aren’t ignoring this. Gemini is integrated into Google Workspace; Copilot is integrated into Microsoft Office. But neither solves the problem.

Gemini can help you write within a document, but most of us realize that it isn’t there yet. Most glaringly, it doesn’t have persistent state across sessions. It doesn’t have access to your other documents unless you manually paste them in. There’s no MCP integration. The agent can’t write back to a file you control.

Microsoft’s Copilot story is similar. It can assist within a document, but it doesn’t operate autonomously across files. It doesn’t checkpoint progress. It doesn’t fit into the agentic flow.

These are AI features bolted onto human-centric tools, not agents operating on a stack. The disconnect remains. If and when they get there, I imagine that we will experience a huge transformation in the way that people work.

Open Questions: Where Does This Go?

I don’t have all the answers here. But I have questions that I think are worth asking.

Should technical docs abandon Google Docs?

Markdown, Notion, and other text-first formats play better with agents. They’re diffable. They’re version-controllable. They can live in a git repo alongside code. An agent can write to them directly.

But organizations have formatting standards, templates, approval workflows. Executives expect slide decks that look a certain way. Legal requires documents in specific formats. The inertia is real.

Is there a bridge? Maybe something that lets agents work in Markdown while syncing to Google Docs for human review? Or does the format have to change entirely? I suspect we’ll see experimentation here, and the winners will be formats that serve both humans and agents well.

How do we handle multi-artifact workflows?

My project required a doc, slides, and a spreadsheet, all in sync. When I updated a section of the doc, the corresponding slide needed to change. When I added a task, the spreadsheet needed a new row.

No tool handles this gracefully today. Each artifact is its own silo. The synchronization is manual.

The answer might be a “project” concept: a container that treats doc, slides, and sheet as a unit, with the agent maintaining consistency across them. Claude Cowork’s folder-based approach hints at this. But we’re not there yet.

What does the enterprise knowledge stack look like?

Delphos is simple. Our context sources are code, meeting transcripts, Notion, and Linear. Everything fits in a few MCPs.

But what about a law firm? Their context sources are contracts, case files, discovery documents, court filings, client communications. What about a consulting firm? Client decks, financial models, research reports, engagement letters.

This is where vertical AI tools are emerging. Harvey AI is the canonical example for legal work: it’s trained on case law and firm-specific knowledge, integrates with LexisNexis and Microsoft 365, and can be up to 80x faster than lawyers at document analysis. Harvey isn’t a general-purpose chatbot. It’s a specialized context layer for a specific profession, with the compliance, security, and workflow integration that profession requires.

The same pattern is appearing across domains. Healthcare has AI tools trained on clinical guidelines and HIPAA-compliant data. Financial services has agents fine-tuned on regulatory frameworks like Basel III. The stack generalizes, but the context sources are domain-specific.

For individual knowledge workers, the equivalent is personal context management. Writers and researchers face a version of the same problem: how do you maintain access to everything you’ve read, saved, highlighted, and noted? Tools like Readwise Reader are becoming AI-powered second brains. Readwise’s Ghostreader lets you chat with your entire highlight library, ask questions across books you read months ago, and generate themed reviews without manual tagging. Perplexity Spaces offers something similar for research: you can organize searches, upload documents, and set custom AI instructions per project, building a persistent context layer for ongoing work.

I use Zotero to track the papers that we are reading at work, and plugins are starting to add AI capabilities for literature review and synthesis. The pattern across all of these tools is the same: they’re solving Layer 1 by building specialized context sources that an agent can query.

The stack pattern should generalize. Context sources, persistent state, agentic flow. But the specific tools and integrations will look different for every organization and every individual. Building these out is a massive opportunity.

Who builds the feedback layer for non-code work?

This is the question that keeps coming back to me.

Code has tests, linters, formatters, type checkers. When an agent writes code, it gets immediate signal on whether the code is correct. That’s what enables the Ralph loop. That’s what lets you walk away.

What’s the equivalent for a design doc? A strategy deck? A grant proposal?

Right now, the feedback layer is the human. You read the output and decide if it’s good. But that doesn’t scale. It doesn’t let the agent self-correct. It keeps the human as the bottleneck.

This is where Data Science matters. Building measurement and feedback systems is core to the discipline. Evals, metrics, automated checks. Someone needs to build the “linter for prose,” the “test suite for slides.” It’s not obvious what that looks like, but I’m convinced it’s coming.

Conclusion: The Manager Model, Extended

In my previous post, I wrote about how LLMs provide a general model for knowledge work: perception, reasoning, action, adaptation. The manager’s job is to set context, provide feedback, and maintain quality standards. The human doesn’t do the work directly. The human guides.

I lived that model for three days. The AI drafted. I directed. And when it worked, it was extraordinary.

But the tooling isn’t there yet. Not for knowledge work outside of code.

The stack is what makes the manager model tractable:

- Good context sources mean less time hunting for information

- Persistent state means less time recreating progress

- Agentic flows mean more time reviewing, less time executing

- Feedback layers, including specialized subagents, mean the agent can self-correct and the human can step back

For software engineering, this stack is nearly complete. You can run a Ralph loop and walk away. For everything else, we’re still building.

Claude Cowork, Jupyter MCP, OpenCode, and the subagent pattern are early moves in this direction. The persistent state problem is being solved. The agentic flow is becoming accessible. The feedback layer remains the frontier.

The future of knowledge work is the manager and the agent, working through a stack that makes both more effective. We’re not there yet. But we’re closer than we were last week.

Tools Used

- ChatGPT with connectors for the original design doc

- OpenCode for drafting and editing this blog post

- Claude Sonnet 4 via OpenCode’s subagent pattern for editorial review

- Fellow for meeting notes and context

- Anthropic’s image generation for diagrams